Emulation

Enlightenment

thinking and changing medical opinion had a profound impact on the use and

design of spas in 18th century Europe (including Britain). The

traditional spa treatment practiced since Roman times was bathing. Drinking the

waters is a much younger practice, introduced in the course of the 17th

century and becoming more dominant in the 18th. Bathing was not

abolished entirely but significantly reduced (instigated by discussions about

the permeability of human skin and hence the ability of the water to get into

the body). This shift in medical theory and practice had crucial implications

for the rhythm and character of spa life and for the infrastructure of spa

places. The new spa routines were part of a larger dietetic regime and would

look approximately like this:

- getting up early in the day (6ish), going to the well and drinking the prescribed amount of water

- in-between the cups one was supposed to drink, and afterwards for at least an hour, walking was necessary, preferably in good company

- breakfast at about 9am, and then again some fresh air and exercise which could mean walking, but also hiking, hunting, or light sports

- lunch and rest afterwards

- for some patients a bath, for others a second round of drinking in the afternoon, and then again rest and good company

- evening meal, some reading or entertainment, early bedtime.

Fresh air, aesthetic enjoyment and

sociability had become part of the therapy. Almost as

important as the springs themselves was now their environment: a pleasant

landscape, space for easy walks, preferably a promenade leading from and to the

spring or pumping station, and a variety of public rooms for communal activities

such as eating together, dancing, conversing, playing cards, games, musical

instruments, even amateur dramatics, and so on. Looking at the histories of

individual spas, we can see that they were either newly created (as demand

grew) or drastically re-shaped and extended in this period. Places like

Pyrmont, Carlsbad, Baden-Baden, Vichy, Montecatini Terme etc., but also

Bath, owe their current shape and design to this development: thus the

foundations for a modern spa culture were laid.

![]()

![]()

Left: promenade in Pyrmont, right: the covered promenade in Marienbad

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

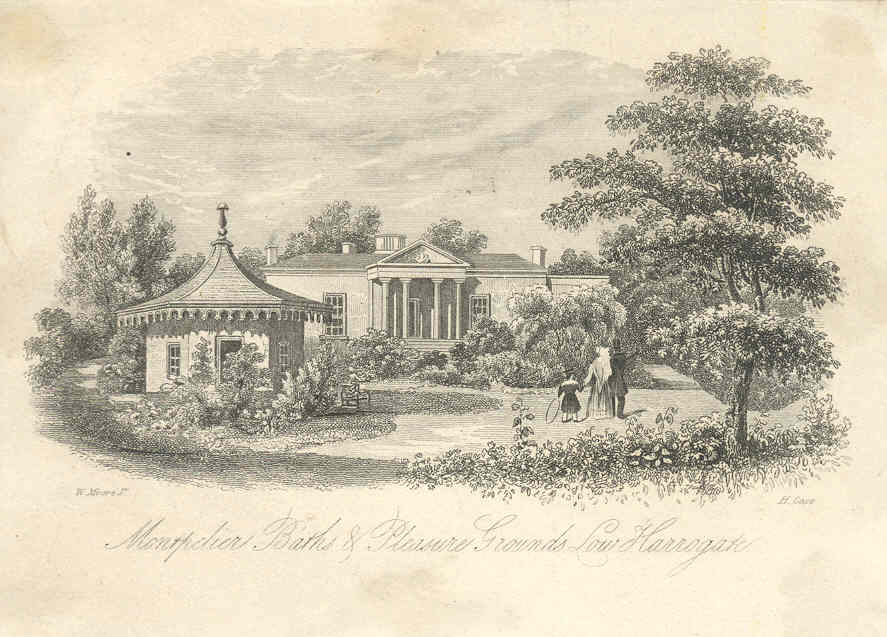

Harrogate

developed as it did to keep step with these wider trends. The Promenade Room (today the Mercer Gallery) was

constructed in 1806 to create a large, central space indoors in which to

promenade, often to the accompaniment of music. It also acted as an Assembly

Room, hosting balls, lectures and other sociable events. In 1835, landscaped

pleasure grounds were created around the Montpellier Baths, and a terrace and

gardens were laid out to the rear of the Royal Promenade and Cheltenham Pump

Room, accessed by glazed doors at the far end of the grand saloon, where rose

gardens and bandstands offered an elegant environment for promenading. Later in

the century, the Valley Gardens, occupying an area of ground known as Bog’s

Fields, were created on the model of the continental Kurpark.

Image © Royal Pump Room Museum, Harrogate Borough Council

When building work was

underway on the foundations for the Montpellier Baths in 1833, six new mineral

wells were discovered. One of them resembled in its composition the Rakoczy Quelle in Bad Kissingen, a famous Bavarian spa. In naming it

Kissingen Well, proprietor Joseph Thackwray

is likely to have wanted to garner the prestige accruing from association with

this long established resort. In this, he was merely repeating what Cheltenham

and other British spas had already done by naming

various elements of their spa infrastructure after

the French town of Montpellier which had long been celebrated for its services to

health.

![]()

![]()

Left: Analysis

of the Kissingen Well by R. Hayton Davis, 1884

Right: Montpellier, France, Source: Wikimedia Commons

Right: Montpellier, France, Source: Wikimedia Commons

As mentioned before, entertainment was an integral part

of the spa experience. When Thomas Gordon was tasked with managing the musical

entertainment in Harrogate’s Spa Rooms (later the Royal Spa Concert Rooms), he

made a point of offering high-quality concerts

and engaging orchestra players and soloists of national and even

international acclaim. ‘The greatest occasion of all must have been that of 6th

October 1849, when the artists were Henrietta Sontag (for whom both Weber and

Beethoven wrote major parts); Lablanche, for whom Schubert wrote songs, […] and

Thalberg. […] Short of attracting the ailing Chopin to Harrogate, or Liszt,

Gordon could scarcely have found greater artists than he did.’ (H. H. Walker) He thus fashioned a concert culture that was equivalent to that

offered in Baden-Baden’s Maison de

Conversation.

![]()

![]()

Musicians Henrietta Sontag (1806-1854) and Sigismund Thalberg (1812-1871)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Image © Royal Pump Room Museum, Harrogate Borough Council

Image © Royal Pump Room Museum, Harrogate Borough Council

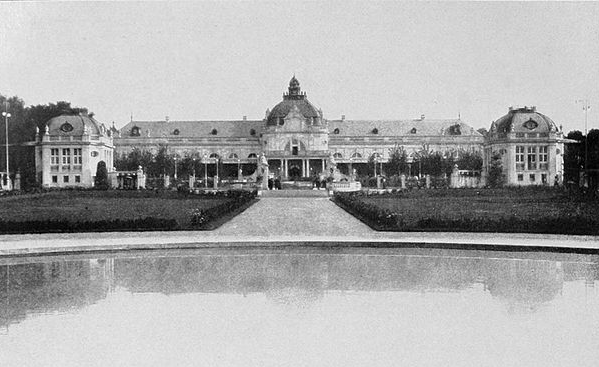

Another continental import was the Kursaal (later: Royal Hall). As

early as 1841 Augustus Bozzi Granville, in his Spas of England, had suggested that Harrogate might benefit from

the erection of a kursaal building in

its centre, which would combine various functions such as dining hall, assembly

hall, music hall, theatre, casino, and even hotel. Half a century later, this

suggestion was put into practice. In doing this, Harrogate ‘broke with the

established British spa tradition, moving quite deliberately toward the

continental manner.’ (F. L. Wright) The preparation for the project entailed

the minute inspection of several continental specimens. Then, after a

downscaling of the plans to match the available funding, construction work

began in the spring of 1901, with the official opening taking place on 28 May

1903. The building was surrounded by a whole complex of public spaces –

gardens, walkways, bandstands, tennis courts – designed for mingling, exercise

and relaxation. This too was in conscious emulation of continental models.

Visited in preparation for Harrogate: Kursaal buildings in Ostend (top), Bad Oeynhausen (bottom left) and Marienbad (bottom right)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

With regard to the strictly medical side of the

spa, too, Harrogate looked to the continent. The variety of its wells allowed

it to diversify the treatments on offer by taking up some new developments. The British Medical Journal of

July 1919 reports that: ‘In order

to make the best use of these mineral waters the Harrogate Corporation […] has

spent nearly a quarter of a million pounds on the provision of modern bathing

establishments. Besides the local sulphur water baths, apparatus for almost

every approved balneological and electrical treatment has been set up […]. At

the Royal Baths more than seventy different baths, packs, douches,

massage-douches, electrical treatments, and accessory treatments are given by

trained attendants.’ And

in order to spread the word about this among the members of the medical

profession, discounts were offered and information materials printed.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Images (right and centre) © Royal Pump Room Museum, Harrogate Borough Council; (left): Wikimedia Commons

Whilst the number of visitors from abroad never grew very

large, there were performers and craftsmen who came over for business, and some

of them stayed, giving Harrogate a special kudos. Notable instances of this

were the Italian Antonio Fattorini who opened a jewellery shop in Harrogate in

1831 to take advantage of the seasonal trade; and dressmaker Louis Cope whose

Jewish family had come from Poland to London, and who settled in Harrogate in

1914. Having initially moved here for reasons of health – he suffered from

asthma – he realised the business opportunities and became a big player in the

fashion industry. And there was of course Fritz Bützner (later Belmont) who

came to Yorkshire from Switzerland in 1907, worked as a chocolatier in

Harrogate from 1912, and founded Betty’s Tearooms

in 1919. Interestingly, it is today of course a very English institution.

![]()

![]()

Left: Betty’s tearooms, right: Fattorini’s jewellery shop

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

From Kursaal, p. 29